Home » Health News »

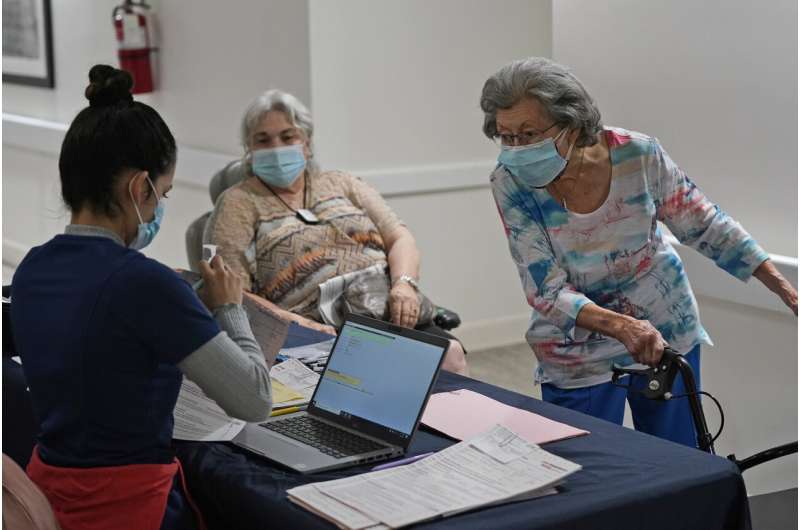

Anxiety grows as long-term care awaits COVID-19 vaccines

Frustration is building over the pace of COVID-19 vaccinations at long-term care sites, where some homes still await first shots while fending off a virus that can devastate their residents.

The major drugstore chains tasked with giving shots in these places are far along in vaccinating nursing home residents and staff. But some other types of group residences won’t receive first doses until mid-February or later, despite being among the top priorities for shots.

CVS and Walgreens have started a massive vaccination push in nearly all states, and they say they are proceeding on schedule. But resident advocates and experts are anxious about delays in delivering vaccines that have been available for more than a month.

“Every week that you wait and you’re not vaccinating is a big deal here,” said David Grabowski, a health policy professor at Harvard Medical School. “My sense is that this process is still going too slow.”

Government officials placed long-term care residents and staff among their top vaccination priorities after they authorized the emergency use of shots from Pfizer and Moderna late last year. That includes both nursing homes, where residents get 24-hour-a-day medical care; assisted living facilities, where people generally need less help; and other types of group homes.

Vaccinations then proceeded quickly in some states like West Virginia, which didn’t rely on the drugstore chains, and Connecticut.

But—as with other aspects of the rollout—the results have been choppy overall. In many places, home operators and residents’ relatives have watched with frustration as states opened vaccine eligibility to other populations before the work in long-term care homes was finished.

Laura Vuchetich says her elderly parents live in a Milwaukee assisted living community and need shots badly. But they have been told they won’t get them until the middle of February even as pharmacies have started handing out hundreds of doses to younger people, including a friend of hers in good health.

“They’re supposed to be at the front of the line,” she said. “They’re in the mid 80s, and my mom had a heart attack last year. It’s just baffling to me.”

Such homes have been hit hard by the coronavirus.

A federal government study last fall found that an average of one death occurred among every five assisted living facility residents with COVID-19 in states that offered data. That compares with one death among every 40 people with the virus in the general population.

The government tasked CVS and Walgreens with administering the shots to long-term care locations in nearly every state. Each vaccine requires two shots a few weeks apart, and CVS and Walgreens say they have wrapped up first-dose clinics in nursing homes.

The chains plan three visits to each location. CVS spokesman TJ Crawford said most residents will be fully vaccinated after the second visit, and the vast majority of assisted living facilities and other residences will have their third visits by mid-March. Some clinics will wrap up in April.

While they wait, the people working and living in those locations are stuck in limbo, hoping the virus doesn’t spread to them or return, said Nicole Howell, who runs a California-based non-profit that advocates for long-term care residents.

“They are essentially standing at the front door fighting this disease with sanitizer and limited staff,” said Howell, executive director of Ombudsman Services of Contra Costa, Solano, and Alameda counties.

Severine Petras watched a COVID-19 outbreak develop at a Pennsylvania assisted living home her company operates a couple weeks before the first vaccines arrived. The Priority Life Care CEO said the recent outbreak hit a “significant” amount of staff and some residents, including one person who died.

Vaccine scheduling has been slow in that state, she said.

“We should have had at least one round of vaccinations in there,” she said. “It would have helped tremendously.”

Petras said she’s frustrated in part because it was widely known that COVID-19 cases would surge after the holidays. She wishes vaccines had been scheduled sooner to protect against that.

As of Sunday morning, 3.5 million doses have been given in long-term care facilities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s about one-third of the roughly 10 million vaccines that Grabowski estimates will be needed to fully protect residents and employees.

“It almost feels like we went about this backwards where they contracted with the pharmacies and let set up the schedule versus saying, ‘Here’s the schedule that you need to meet,'” he said.

The drugstore chains have faced several challenges. At some locations, a high percentage of staff have declined the shots on the initial visits. The companies also had to set up thousands of clinics and reschedule some at locations where COVID-19 outbreaks developed.

CVS and Walgreens say states determined when they could start giving shots at assisted-living facilities, and they have finished first-dose clinics when they were allowed to begin in December. But other states didn’t allow them to start until mid-January. They also say they are pouring thousands of employees into the effort.

Even so, Grabowski and Howell say outside assistance still may be needed to speed up the effort in some areas.

In New York, the Empire State Association of Assisted Living contacted state regulators because some homes had initial clinics scheduled in March, Executive Director Lisa Newcomb said. Those clinic dates were then moved mostly to late January.

“We had some members who were very, very upset about having to wait until March,” she said.

In Florida, the state brought in an outside company to help deliver vaccines if the drugstore chains weren’t able to schedule a first clinic until late January.

Innovation Senior Living CEO Pilar Carvajal said the company called one of her homes that hadn’t had a clinic date set yet and showed up the next day to start delivering shots.

She said vaccinations should be complete at her six Florida assisted-living facilities by the end of March. Then she can stop worrying about employees bringing the virus to work after doing something as simple as going out to eat.

Source: Read Full Article