Home » Health News »

Eating for health: how dietary interventions impact pre-diabetic oral and gut microbiome, metabolites and cytokines

In a recent study published in Nature Communications, researchers evaluated the impact of two diets on the intestinal and oral microbiota, cytokines, and metabolites of 200 pre-diabetic individuals.

Pre-diabetes, characterized by increased glucose levels in the blood but below the threshold for diabetes, is a major risk determinant for diabetes mellitus type 2 and renal and cardiovascular diseases.

Inadequate nutrition, increased intake of processed meat, low-quality carbohydrates, sugary beverages, and a lower intake of plant-sourced foods can give rise to insulin insufficiency and pancreatic β-cell injury.

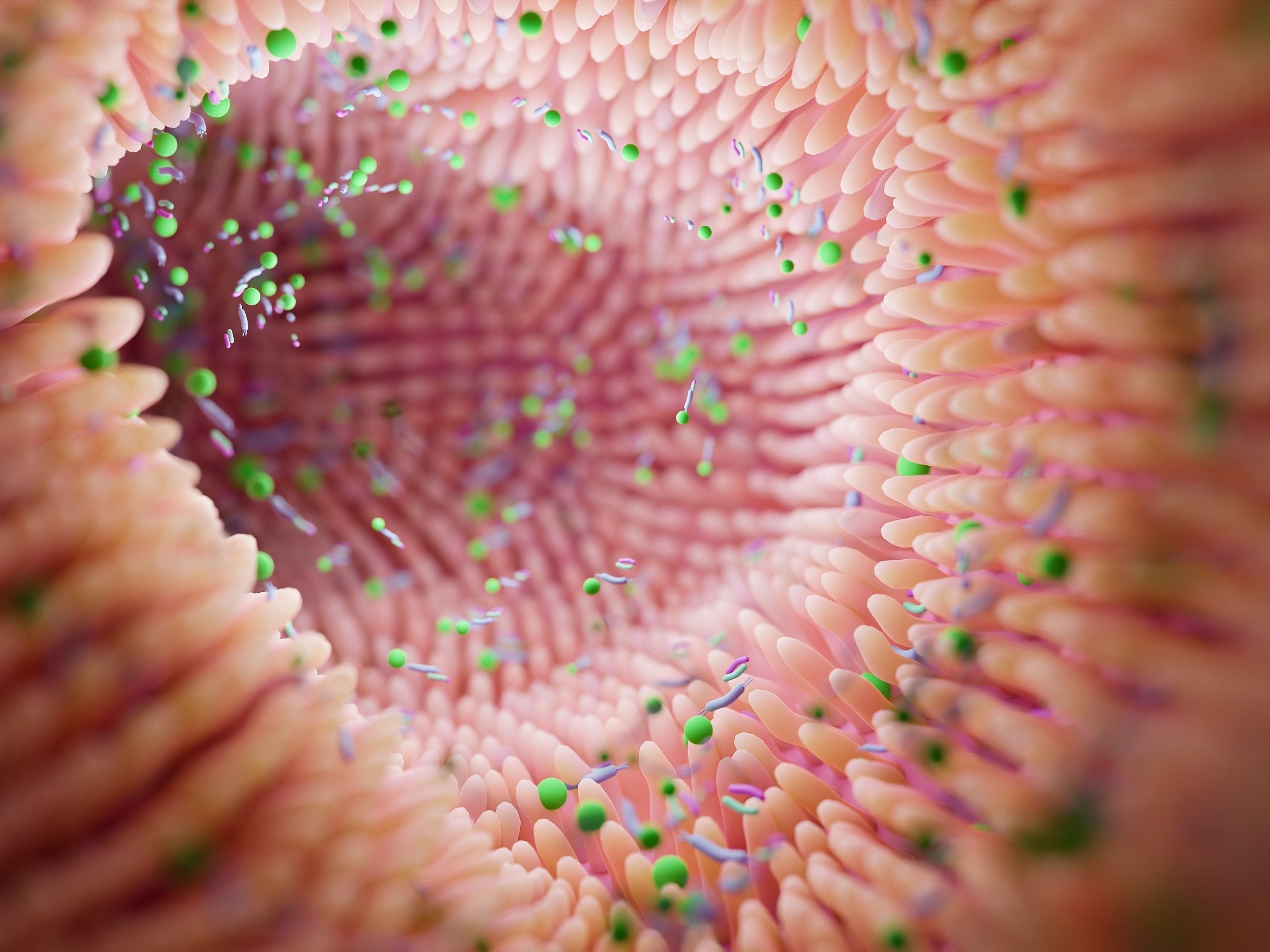

The gut microbiota mediates this relationship, deriving energy from indigestible foods and generating cytokines and metabolites. The oral microbiota is linked to hyperglycemia due to chronic periodontal inflammation.

About the study

In the present study, researchers evaluated the effects of personalized post-prandial glucose-targeting diets (PPT) versus the standard Mediterranean (MED) diet on the gut and oral microbiota and serological cytokines and metabolites among individuals with pre-diabetes.

In total, 225 individuals were recruited for the study, with 113 and 112 randomly allocated to the PPT and MED groups, respectively. The research, however, had 200 individuals, 100 from both groups. Individuals were observed for six months during the intervention phase and for two 14-day periods of follow-up.

Anthropometric measurements, a continuous glucose monitoring device (CGM), self-documented food consumption digital records using a mobile phone, and the collection of blood, feces, and subgingival plaque samples for short-read sequencing were used to collect data.

The PPT dietary intervention used machine learning (ML)–based algorithms assessing the nutritional content of meals, anthropometrics, blood tests, lifestyle, and intestinal microbiota variables to estimate an individual's postprandial glycemic response. The Mediterranean diet advocated in national recommendations as standard care for individuals with pre-diabetes, served as a control.

Grains, wheat bread, vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, olive oil, low-calorie dairy, and poultry products were recommended to the MED intervention participants, whereas pastries, sweets, processed meat, fried and fatty foods, high-calorie dairy, and bakery products were discouraged.

The researchers evaluated the impact of each diet on 336 oral and 605 gut microbial species, 311 oral and 380 gut microbial pathways, 1,095 serological metabolites, and 76 cytokine characteristics in samples taken before and after the intervention.

The researchers also assessed whether microbial functions altered significantly in response to the dietary changes by calculating pathway relative abundance at baseline and comparing it to the end of the intervention for each diet independently. Shannon’s alpha diversity index was used to analyze changes in microbial diversity. Metabolite concentrations in serum were determined using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

The quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) proximity extension assay (PEA) was used to measure cytokine levels. A mediation analysis was performed to investigate whether the microbiota mediated the effect of dietary changes on glycemic, metabolic, and immunological measures.

The researchers additionally examined whether microbial species influenced the impact of diet on blood metabolites. Lastly, they investigated whether the effects of food on cytokines were mediated by microbial species.

Results

The findings indicated that the microbiome plays a significant role in the effects of diet on glycemic, metabolic, and immune measurements. The gut microbiota compositional change accounted for 12% of the serum metabolite variance.

PPT group participants showed a statistically significant increase in their dietary lipid consumption by 14.8% and lowered carbohydrate intake by 17.8%, while MED group participants significantly reduced their lipid consumption by 4.5% and elevated carbohydrate intake by 2.1%.

Both interventions led to significant increases in protein intake, with the PPT intervention causing a larger alteration compared to the Mediterranean intervention in macronutrient components.

The PPT intervention had pronounced effects on glycemic regulation, as evidenced by the glycated hemoglobin values and glucose levels in the blood. However, the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) findings showed non-significant differences between the diets.

Seven gut pathways changed solely in the PPT diet, including a significant increase in β-(1,4)-mannan polysaccharide degradation, D-fractionate and β-D-glucuronoside degradation, gluconeogenesis, anaerobic energy metabolism, nitrate reduction, and putrescine biosynthesis.

In the MED intervention group, 27 metabolites significantly increased, including 10 uncharacterized biochemicals, seven lipids, and six amino acids, along with a xenobiotic (3-bromo-5-chloro-2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid), peptide (HWESASXX), nucleotide (dihydroorotate), and bilirubin.

Among PPT diet participants, one cytokine, stem cell factor (SCF), significantly increased. Among MED diet participants, the Sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) and Axin 1 (AXIN1) cytokines significantly increased.

Among PPT group participants, there was also a significant elevation in C-X-C3 motif chemokine ligand 1 (CX3CL1) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 11 (CCL11), positively associated with diabetes, and in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) that protects against the disease by immunological modulation. In addition, among MED diet participants, a statistically significant elevation in STAM binding protein (STAMBP) and sulfotransferase 1A1 (ST1A1) was observed.

PPT group individuals showed statistically significant increases in the intestinal microbiota richness (11 species), diversity (0.3), and human cellular shedding (−0.1% reads in one microbiota sample). The MED intervention led to significant elevations in Clostridiaceae and Ruminococcaceae abundance and a statistically significant reduction in that of the Eubacteriaceae species.

The oral microbiota was genetically more dynamic than the gut microbiota, with the most replaced species being Leptotrichia buccalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Actinomyces naeslundii.

Conclusion

Overall, the study findings highlighted the importance of the microbiome in influencing the effects of diet on glycemic, metabolic, and immune measurements, particularly concerning diabetes.

- Shoer S, et al. (2023). Impact of dietary interventions on pre-diabetic oral and gut microbiome, metabolites and cytokines. Nat Commun, 14, 5384. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41042-x. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-41042-x

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Medical Condition News

Tags: Apoptosis, Assay, Blood, Bread, Carbohydrate, CCL11, Cell, Chemokine, Chromatography, Chronic, Cytokine, Cytokines, Diabetes, Diabetes Mellitus, Diet, Fish, Food, Gluconeogenesis, Glucose, Glycated hemoglobin, Hemoglobin, Hyperglycemia, Inflammation, Insulin, Ligand, Lipids, Liquid Chromatography, Machine Learning, Mass Spectrometry, Meat, Metabolism, Metabolite, Metabolites, Microbiome, Necrosis, Nucleotide, Nutrition, Olive Oil, Polymerase, Polymerase Chain Reaction, Protein, Research, Spectrometry, Tumor, Tumor Necrosis Factor, Vegetables, Wheat

Written by

Pooja Toshniwal Paharia

Dr. based clinical-radiological diagnosis and management of oral lesions and conditions and associated maxillofacial disorders.