Home » Health News »

Lessons from Katrina on how pandemic may affect kids

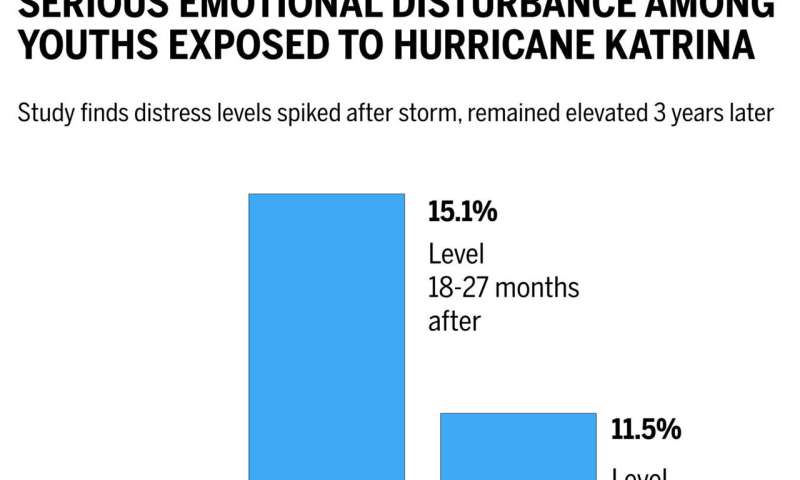

Hurricane Katrina caused widespread destruction and more than 1,800 deaths in 2005, much of it in New Orleans. Though a tragedy, psychologists recognized the storm and its aftermath provided an opportunity to better understand the impact such calamities have on children. One such study was conducted by Harvard researchers under lead author Katie McLaughlin, the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences, and senior author Ronald Kessler, Harvard Medical School’s McNeil Family Professor of Health Care Policy. It found that cases of serious emotional disturbance—such as anxiety, depression, or inappropriate behavior significant enough to negatively affect a child’s school performance and everyday life—were nearly triple pre-storm levels more than two years after Katrina.

The Gazette spoke with McLaughlin, a psychologist who continues to study the impact of trauma—including the pandemic—on children. McLaughlin spoke about lessons learned from Katrina that could be applied to the current situation and what that might mean for the mental health needs of America’s children in the years to come.

Q&A: Katie McLaughlin

GAZETTE: You were the lead author of a study of serious emotional disturbance in youth after Hurricane Katrina. What were the lessons of that study?

MCLAUGHLIN: One of the things we observed in that study is quite consistent with other research on natural disasters, terrorist attacks, other types of community-level, stressful events that lead to widespread disruption. First, a piece of good news, which is that most children afterwards are doing fine. They are not experiencing high levels of emotional distress; they don’t meet criteria for a mental disorder. That is very consistent with what we see following major life stressors of many kinds: on average about half of kids are going to weather those stressors without developing meaningful mental health problems or symptoms of mental disorders.

GAZETTE: When we’re talking about life stressors here, are we talking about the kinds that would happen in during any time, like death of a parent or a job loss of a parent, or something more unique and large-scale?

MCLAUGHLIN: This work focused on community-level disruptions, like a natural disaster or severe life events—having a parent die, being exposed to significant violence, being in a life-threatening car accident—where the severity of the stressor is very meaningful. What we’ve learned across lots of different studies is that the most common pattern is resilience—at least half of children develop no meaningful mental health problem even after significant adversity. The less-good news is that the remaining kids tend to experience some elevation in mental health problems. Across studies, you see that 20 to 25 percent develop symptoms of anxiety or depression or an increase in behavior problems that are relatively transient. Typically, within about a year, they come back down to baseline. The other 25 to 30 percent of kids are the ones that we are more concerned about. They develop symptoms that are staying elevated over time. They’re not coming back down to baseline right away, or even a year or two years after the event.

GAZETTE: Were those more general results reflected in the Katrina study?

MCLAUGHLIN: For the study of children exposed to Hurricane Katrina, we used a fairly stringent definition of mental health problems. “Serious emotional disturbance” essentially reflects that not only are these kids having symptoms and mental health problems that we would consider severe enough to classify as a mental disorder—for example, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder—but also that those symptoms are really causing problems in their lives.

This is an important distinction because a lot of us are experiencing more symptoms of mental health problems right now, like feeling more anxious than usual. Where we get concerned, from a clinical perspective, is when those symptoms begin to interfere with our functioning, make it hard for us to do our job or schoolwork, or cause conflict in our relationships.

In the Hurricane Katrina study, we found that about 15 percent of kids met criteria for serious emotional disturbance more than a year after the hurricane. These are kids who are being stably impacted even once a fair amount of time has passed. They’re still doing less well than they were before the hurricane.

GAZETTE: Are you surprised at how high that was a year-plus later?

MCLAUGHLIN: Yes and no. Yes, in that one in six children experienced persistent mental health problems after the disaster. However, that is pretty consistent with what we see generally following these kinds of major community-level stressors. And Katrina, relative to other natural disasters, was a severe stressor. The families who participated in the study were largely from the New Orleans area where there was massive community disruption. Depending on where you lived, there was not only widespread destruction of homes, but a massive migration out of the area. A lot of families who lived where the damage was severe chose not to rebuild and relocated. So you had the dissolution of social support networks—kids going to different schools, losing their friends, people losing their church community, and the loss of many supports that we know are really important buffers against developing mental health problems in the face of stress. That, I think, made it harder for people to cope. So I think it’s somewhat unsurprising that we saw persistent problems for a fairly meaningful proportion of kids given the amount of disruption in their lives and the loss of these natural support systems.

GAZETTE: You followed up on that study a couple of years later?

MCLAUGHLIN: That’s right. We saw—another year down the line—the rates of serious emotional disturbance decline. Even some of those kids who were persistently elevated two years after the disaster eventually recovered. But what we saw in terms of who continued to recover and who didn’t was a pattern that I think is really important to highlight as we think about the likely impacts of COVID.

We found that the kids who are most likely to develop these lasting mental health problems are those who had the highest exposure to stressors related to the hurricane. So if your house was destroyed, if you had to sleep in a church basement or in the Superdome because your house got flooded, if you lost a family member or a friend, if you got seriously injured, if your family had a hard time meeting basic needs like food and shelter after the hurricane, the more of those stressors you experienced, the more likely you were to meet criteria for this sort of persistent mental health challenge after the disaster.

GAZETTE: How do those results apply to today and COVID?

MCLAUGHLIN: When we think about COVID, we try to think about which families are likely to be at higher risk.

My lab has been doing ongoing studies of families who we had been following prior to the pandemic and have followed up with several times during the pandemic to see how the kids are doing in terms of their mental health. Thirty percent met criteria for clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety or depression prior to the pandemic and 20 percent met criteria for clinically meaningful externalizing behaviors, like conduct problems, hyperactivity, and inattention. In contrast, two-thirds, 67 percent, had clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety or depression and 67 percent exhibited clinically meaningful externalizing problem behaviors when they were re-assessed during the pandemic. Consistent with the work I just described, what we see is that by far the biggest predictor of which kids are having increased symptoms of mental health problems like depression, anxiety, and behavior problems are the kids who have been exposed to the highest levels of pandemic-related stressors.

These are the families where somebody has gotten ill with COVID or died, or who have had major financial stressors—either loss of income for a parent or difficulty meeting basic needs like food and shelter. These are families who’ve had exposure to discrimination related to the pandemic, are experiencing severe conflict in relationships with someone they live with or disruptions in relationships with peers and teachers. These are kids whose home environments are crowded and less conducive to being able to do remote schooling. These are just a few examples, but the more of these experiences that pile up, the more likely the child is to have experienced an increase in mental health problems during COVID.

GAZETTE: So, with 500,000 dead and 28 million cases today, what can we project about the severity of needs post-COVID?

MCLAUGHLIN: Again, there are both reasons for optimism and cause for concern.

On the optimistic side, as I said, we typically see that about half of kids are doing fine and are resilient despite encountering significant adversity. Is that going to be true in COVID? That’s a reasonable question because there are a number of things about the pandemic that are different than natural disasters we’ve studied in the past. This is much more widespread; it’s not localized to a particular city or particular state where a hurricane has happened. This is happening to everybody all at once so the scale of exposure is much higher. The other thing that’s different about the pandemic is that the disruptions in daily life have been much more persistent over time. After major natural disasters it takes a while for communities to rebuild, but they do. And some things get put into place much more quickly than others. Typically kids are going back to school—even if it’s a different school—relatively quickly. What we’ve had so far is a year—and who knows how much longer—of major disruption to daily life for all of us and for kids in particular, especially kids who have been not going to school and learning remotely, not engaging in their normal activities with peers. We don’t know the impact that that more persistent and widespread exposure is going to create. One can guess that the degree of mental health problems that emerge is going to be larger, although we don’t know for sure.

GAZETTE: Can the mental health care system handle many more cases? I’ve heard it’s running pretty close to full capacity right now. Even if you just look at those who might have lost someone, with 500,000 dead already, that’s a lot of kids.

MCLAUGHLIN: What we saw in Katrina was the single stressor that had the largest impact on kids in terms of developing persistent elevations in mental health problems was having a family member die. So, when we focus on the number of lives lost, that might be just the tip of the iceberg, but those are likely the kids who are going to be most severely impacted in terms of mental health.

Can the system handle it? It’s a great question. My expertise is really not in models of care. Given my experience as a mental health professional, though, we have always had a lack of well-trained mental health providers for children. There’s a real problem of access, especially for families who have lower socioeconomic status and don’t have access to insurance plans that provide good coverage for behavioral health services.

The field is desperately in need of new models of care to improve access. Two of the most promising are thinking about ways to get mental health providers to the places where kids are already spending time. So thinking about how we can consistently provide services within schools, ways that are low-cost, is one direction. Embedding a mental health provider within a school would provide access to lots of kids who otherwise wouldn’t have access or whose health insurance plans might not provide coverage for mental health services.

Second is integrating mental health services into primary care. There’s actually been a huge movement toward that in adult medicine. People call it behavioral health integration, which basically means co-locating mental health providers in primary care clinics so that when people tell their primary care physician that they’ve been struggling with symptoms of depression or low mood, rather than saying, “Oh, you should really talk to a mental health provider,” they say, “We have somebody right here in this clinic who can talk with you about that. Would you be interested in scheduling an appointment before you leave?”

The integration of mental health services with pediatric primary care has lagged behind adult medicine, but there are increasing calls to begin this kind of integration, and it’s starting to happen. That has a lot of promise for getting more kids connected to services. It’s not going to help everyone. These kids—the 10 percent or so who we saw in the Katrina study who had serious problems that were not getting better—are going to need more intensive interventions involving working one-to-one with a clinician for a more prolonged period of time. But there are going to be a lot of kids who have symptoms that can probably be addressed with brief interventions delivered in settings like school and primary care.

GAZETTE: What should parents look for, as far as behaviors or signs of trouble?

MCLAUGHLIN: Families can look out for meaningful changes in behavior: kids not wanting to participate in things that used to be enjoyable, increased irritability, increased negative emotions or reactivity, difficulty sleeping, trouble concentrating. These are hallmark symptoms that cut across a lot of different mental health challenges. Expressing worries or fears are common ways anxiety gets expressed in children. Often in young children, you see more somatic complaints, persistent headaches and stomachaches or children having a harder time getting along with their siblings, with their parents, or following instructions.

We want to focus on changes in emotional reactions that are persistent. We all are going to experience days, maybe even weeks, where we’re feeling more worried than usual, having more trouble sleeping, but when it becomes a more persistent change for weeks and weeks, that’s when parents should pay attention. It’s also normal to see—especially in young children —transient developmental regression when serious stressors or changes in routines happen. Suddenly kids are wetting the bed when they had stopped, or needing more help and structure; language regression where kids are using fewer words or engaging in behaviors typical at earlier points in their development. Those things are normal reactions when young children experience major stressors, but they tend to get back on track relatively quickly. When you notice changes persisting over time, it might be cause for checking in with a pediatrician or another medical provider.

GAZETTE: How big a difference can the responses of the adults around a child make?

MCLAUGHLIN: One of the very consistent predictors of how well children navigate these kinds of stressors and challenges is how well their parents navigate them. In the Katrina study, we saw that having a parent who was struggling with mental health problems was one of the biggest predictors of the child experiencing persistent difficulties with mental health following the disaster. And we know from research on many other kinds of stressors, that when parents exhibit a lot of distress, when parents are struggling to cope, you see that reflected in their children also being less likely to bounce back or recover after a stressor.

GAZETTE: So keep it together?

Source: Read Full Article