Home » Health News »

Vulnerable children in UK faced a healthcare shortage during the pandemic period

During the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many elective procedures and appointments were canceled or postponed due to the overwhelming burden posed by the caseload of severe COVID-19, as well as the need to implement physical distancing and thus contain viral transmission. This led to reduced hospital visits for many patients.

A new preprint on the server medRxiv* describes the pattern seen among children who needed healthcare during the pandemic, demonstrating how the most vulnerable had a higher rate of care deficits.

Study: Deficits in hospital care among clinically vulnerable children aged 0 to 4 years during the COVID-19 pandemic. Image Credit: L Julia/Shutterstock.com

Background

Children aged 0-4 years, especially those below the age of 1 year, have been visiting hospitals in greater numbers over the past few years, with the increase being more marked in those born preterm, with low birth weights, or with a birth defect. This changed during the COVID-19 lockdown, and again, the decline was most obvious in these groups.

However, the inability to access planned hospital care is likely to affect the diagnosis of treatable conditions or the required preventive or therapeutic measures that could correct existing issues or prevent new ones. This could in turn worsen the child’s health or disrupt normal development.

Conversely, the lower number of unplanned hospital visits could be due to fewer infections, fewer injuries, and fewer health issues, as social contacts were lessened during this period. The researchers in the current study, on the medRxiv preprint server, therefore sought to examine how much of the decrease was due to unmet needs for health care on an unplanned or planned basis.

They used national data collected over time in England, to quantify the rates of planned and unplanned hospital visits, both as outpatients and inpatients. They stratified children by the presence of chronic conditions or risk factors and compared the rates of hospital visits among children with and without these factors, as well as the changes in such visits over time. They also looked at the type of visits, whether in-person or virtual.

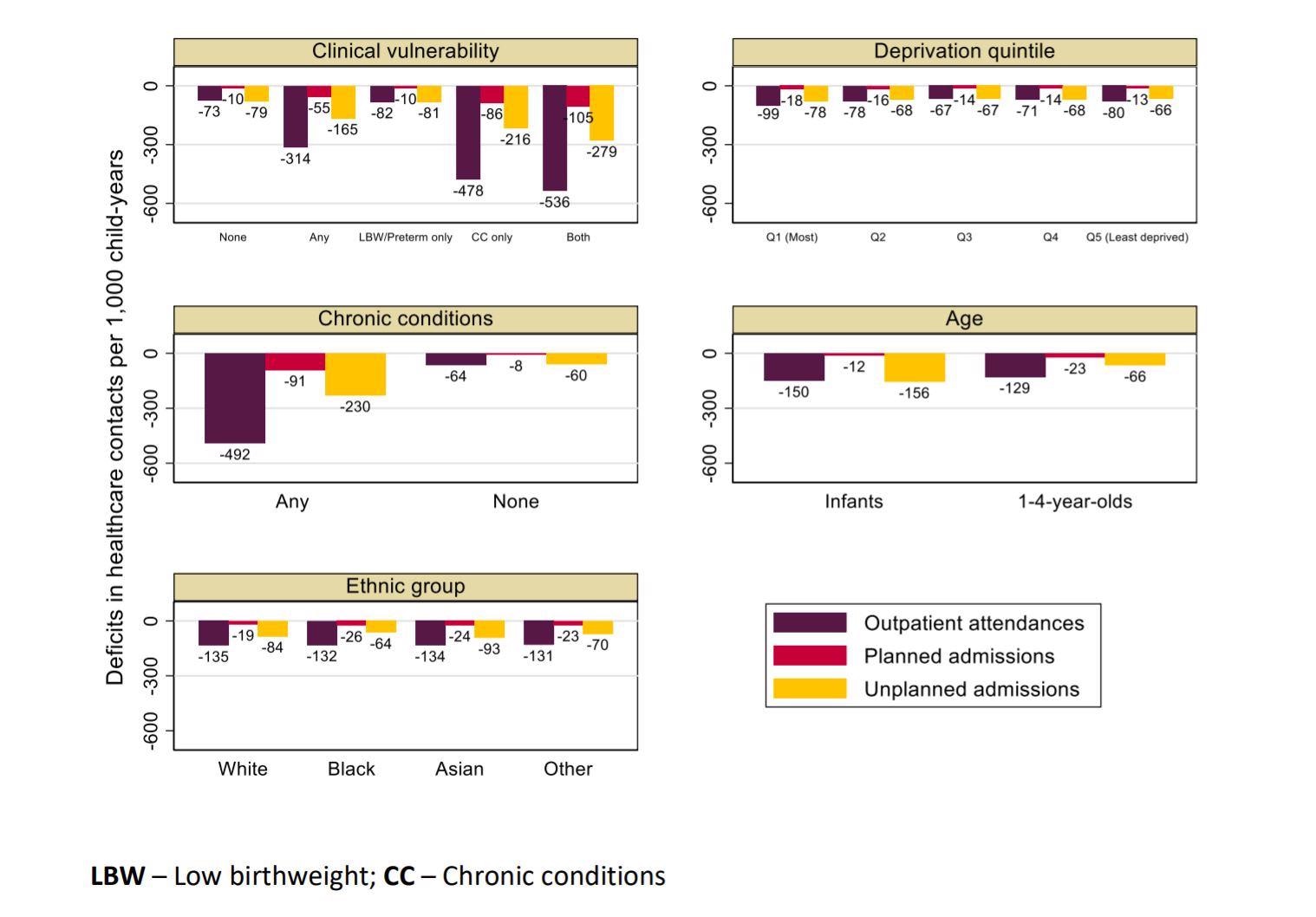

The outcome was defined as the absolute difference in observed and expected rates of hospital visits per 1,000 child-years. This was evaluated against the age, quintile of deprivation from the Index of Multiple Deprivation, and ethnicity of the child.

What Did the Study Show?

The study included over 3.8 million children between the ages of 0 and 4 years, of which one in ten had chronic medical conditions, the same proportion had been born preterm, and 2% had both risk factors. Almost a fifth had one or more vulnerabilities.

The findings showed more contacts among infants, at 60%, vs 8% of those older than this but below 4 years, who had visited the hospital as outpatients at least once a year. Of the clinically vulnerable (CV) group, almost one in three had one or more visits a year, but half of those without such known risk factors.

This was seen to be true overall for all types of hospital care and was highest for those children who had chronic health conditions but were also born prematurely or with low birth weight. Though they made up less than a fifth of the total, half the decline in outpatient visits and planned admissions was in this group, along with a third of the shortage in unplanned admissions.

Among infants, outpatient visits and unplanned admissions were affected more than planned admissions, compared to older children in this group. The most deprived children were a little more affected in both planned and unplanned admissions compared to the least. The first lockdown brought about the largest decline in outpatient visits and unplanned admissions, while the second lockdown period was associated with greater decreases in unplanned admissions.

Outpatient visits and planned admissions went down both before and during the first lockdown for all children with chronic conditions. For infants, the rates went down to pre-pandemic rates, but for older children, it remained below the average for 2015-19 in the third lockdown.

Unplanned admissions decreased to a much greater extent among these children than among healthy children, but did not return to normal across all age groups. The autumn-winter peak was also lower than in previous years, in 2020, but increased once primary schools were reopened in March. The increase was highest for those with chronic conditions, without any difference by ethnicity and deprivation levels.

Planned outpatient visits were canceled or postponed at higher rates over the three weeks before the first lockdown, giving way to teleconsultations. At the end of the study period, in-person visits remained lower than before.

Deficit in care during the pandemic (March 2020-2021), estimated from predicted minus observed rates of hospital contacts per 1,000 child-years for children aged 0 to 4 years, by clinical vulnerability status and risk factors

What Are the Implications?

The findings indicate that under-fives in England had large decreases in both planned and unplanned hospital visits during the pandemic, with the greatest impact being among children at risk because of low birth weight, preterm birth with or without other medical conditions, and the most deprived children.

Almost half the decline for both outpatient visits and planned admissions was among clinically vulnerable children, while the latter also accounted for a third of the shortfall in unplanned admissions. Infant visits showed signs of recovery after the pandemic.

Similar reductions in hospital visits and admissions among children have been observed globally, whether planned care, emergency visits, or emergency admissions. The fact that admissions and visits for emergencies related to asthma and infections went down, in some earlier studies, indicate a true reduction in morbid events, particularly infections, during the lockdown period.

Some evidence was there of unequal impact in the redistribution of healthcare, as shown by reductions among those of Asian origin and the most deprived. In infants, the restrictions appeared to have the lowest effect, which is understandable since most care in this segment requires to be given immediately. The larger gap between expected and actual care in older children indicates that real needs were going unmet, with potential implications for their health over the long term.

Again, children who had the least access to the internet at home would be hit hardest by the shift to virtual appointments.

The reduced incidence of injuries and infections, with associated hospitalizations, is in contrast to the unchanged rates of admissions for non-infectious causes and emergencies such as appendicitis. The reduced chances for the spread of respiratory and gut-related infections due to better hygiene and physical distancing undoubtedly played a role in the former, a view supported by the increase in unplanned admissions once schools reopened.

Reduced air pollution and better compliance with pediatric treatment regimens may also have contributed to this phenomenon of better child health. However, the lower monitoring by healthcare and social workers could have meant that some children slipped through the net, causing delayed or absent medical care. This must be confirmed before it is accepted as a complicating factor, however, as it is purely hypothetical at the present.

Further studies will help find out the extent to which acute-stage presentation at the hospital is associated with missed or late diagnosis. The long-term and immediate complications associated with such deficits in planned care also merit further investigation, especially in children with specific illnesses and the most vulnerable children. This would help shape the evolution of strategies to catch up with these children and allot the required resources as well.

*Important notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Etoori, D. et al. (2021). Deficits in Hospital Care Among Clinically Vulnerable Children Aged 0 To 4 Years During The COVID-19 Pandemic. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.16.21267904. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.16.21267904v1

Posted in: Child Health News | Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Air Pollution, Appendicitis, Asthma, Birth Weight, Child Health, Children, Chronic, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Evolution, Health Care, Healthcare, Hospital, Hygiene, Pandemic, Pollution, Respiratory

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article