Home » Health News »

New study reveals differences in diagnosis of psychiatric disorders between Eastern and Western countries

Psychiatrists diagnose psychiatric disorders by observing a patient’s symptoms and applying diagnostic criteria, such as those in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is widely used in the United States.

However, the diagnostics tests available for psychiatric disorders do not rely on purely objective data, unlike the tests for diseases such as diabetes or conditions like hypertension. As a consequence, the results of a diagnostic test for a psychiatric disorder may be influenced by how the psychiatrist interprets the patient’s symptoms.

While this problem is still prevalent today, we have a few additional tools at our disposal that could soon assist psychiatrists in their diagnoses. For example, genomic studies may be used to identify genes that put a person at a greater risk of developing a specific disorder, although they cannot provide perfect information theoretically.

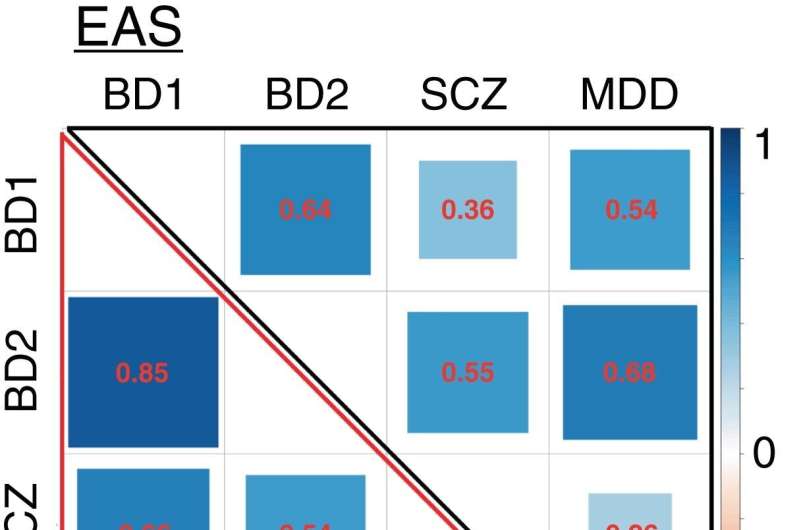

However, genetic correlation analyses have shown that different psychiatric disorders have certain degrees of shared genetic risk. Such were the findings of a recent analysis of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium datasets, for which scientists calculated the genetic correlations between major psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

The abovementioned analysis, however, was conducted on a dataset containing samples from mostly Europeans. This motivated a research team led by Professor Masahi Ikeda of the Department of Psychiatry at Fujita Health University School of Medicine, Japan, to compare these genetic correlations with those obtained from an East Asian population.

The aim was to determine whether there are any marked differences in the results for Eastern and Western people at large, and discuss what the origin of such differences could be. This study was co-authored by Takeo Saito and Nakao Iwata, also from Fujita Health University School of Medicine, and published as a research letter in Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

The researchers focused mainly on bipolar disorders (BDs), which can be classified based on the degree of ‘extreme moods’ as BD subtype I (manic and depressive states) and BD subtype II (hypomanic—which is a milder form of manic—and depressive states). The results of the genomic analysis revealed that in the East Asian population, the genes of patients with BD subtype I were more correlated with those for major depression.

This was in stark contrast with the results for the European population, for which BD subtype I was more genetically correlated with schizophrenia. On the other hand, the genetic correlations between BD subtype II with schizophrenia and depression were similar when comparing the East Asian and European populations.

But why would there be differences in the genetic correlations of BD subtype I with other disorders between different ethnic populations? This contradicts the common disease—common variant hypothesis, which posits that genetic components typical of a common disease should be shared even among different populations. The research team believes that this difference stems from how Japanese psychiatrists diagnose bipolar disorders.

“Japanese psychiatrists tend to be heavily influenced by old German psychiatry and hold that bipolar disorder is a mood problem,” explains Professor Ikeda, “There may thus be a difference in the general diagnostic tendencies between Japanese psychiatrists and Western psychiatrists in that Japanese psychiatrists tend to not diagnose bipolar disorder in patients with delusions or other psychotic features with careful attention.”

Another plausible explanation is that Japanese psychiatrists tend to enroll patients with mood-driven problems more than patients with psychotic features in research on BD. Epidemiological studies on Caucasian populations have shown that patients with psychotic features are half as likely to have BD subtype I, whereas this study on East Asian populations revealed the likelihood to be much lower—as small as 30%.

The bottom line is that these differences in diagnostic (or ‘enrollment’) tendencies should be noted by psychiatrists when analyzing data, especially the results of clinical trials. “We are not trying to say that either diagnostic approach is superior, but rather that if this trend is also occurring in clinical trials, it may affect evaluations of drug responsiveness,” remarks Professor Ikeda, “This is especially true for second-generation antipsychotics, which are presumed to be more effective for symptoms such as delusions.”

Source: Read Full Article